Temporomandibular Joint Disorders

A US group undertook excellent research resulting in separating 3 conditions that are termed TMDs including;

- Arthromyalgia (pain of joint and surrounding muscles)

- Arthritides (arthritis of the joint caused by osteo, rheumatoid or reactive arthritis)

- Dysfunction (clicking, crepitis or locking of the joint)

Clear UK Guidelines for TMDs patient management can be found on Royal College of Surgeons Website is available at: http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/fds/publications-clinical-guidelines/clinical_guidelines/documents/temporomandibular-disorders-guideline-2013. More information on Temporomandibular disorder here.

When a patient sees their dentists or specialist they will be evaluated by taking a history, clinical examination taking less than 3 minutes explained by Dr Stephen Davies at Manchester Dental School here and video below:

Below is the NHS information http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/temporomandibular-joint-dysfunction-and-pain-syndromes

Synonyms: TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome, myofascial pain disorder, myofascial pain-dysfunction syndrome, facial arthromyalgia, craniomandibular dysfunction, Costen’s syndrome

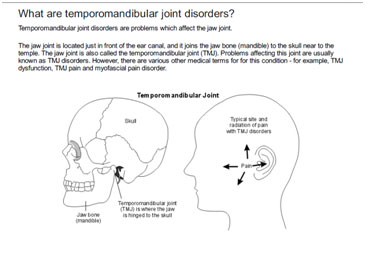

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) refers to a group of disorders affecting the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles and the associated structures. These disorders share the symptoms of pain, limited mouth opening and joint noises.[1]

Epidemiology

Temporomandibular joint symptoms are relatively common. Symptoms of TMDs occur in approximately 6-12% of the adult population.[2] TMDs may occur at any age but are more common in women and in early adulthood.

Aetiology[1]

TMJ disorders are thought to have a multifactorial aetiology, but the pathophysiology is not well understood. Causes can be classified into factors affecting the joint itself, and factors affecting the muscles and joint function. The American Academy of Orofacial Pain has also produced a diagnostic classification.

Factors affecting muscles and joint function – myofascial pain and dysfunction

This type of TMJ problem is most common. Often it is difficult to determine a single cause, but contributing factors may be:

- Chronic pain syndromes or increased pain sensitivity.

- Psychological factors: these may contribute (as with other chronic pain syndromes).

- Muscle overactivity: bruxism (grinding of the teeth and clenching of the jaw); orofacial dystonias.[2]

- Dental malocclusion: this was formerly considered to be an important factor; indeed TMJ dysfunction was often considered as a dental problem. However, the evidence does not support this, and TMJ dysfunction is now seen as a multifactorial problem rather than a dental condition.[3]

Factors affecting the joint

The most common problems are:

- Intra-articular disc derangement (various types)

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

Other problems affecting the joint are:

- Other types of arthropathy – eg, gout, pseudogout or spondyloarthropathy

- Trauma

- Hypermobility or hypomobility

- Infection

- Congenital disorders – eg, branchial arch disorder

- Tumours (rare)

Symptoms[1]

The three cardinal symptoms of TMJ disorders are: facial pain, restricted jaw function and joint noise.

Pain

- Located around the TMJ, but may be referred to the head, neck and ear.

- Pain, located immediately in front of the tragus of the ear, projecting to the ear, temple, cheek and along the mandible, is highly diagnostic for TMD.

PatientPlus

Restricted jaw motion

- May affect mandibular movement in any direction.

- Jaw movements increase the pain.

- Patients may describe a generally tight feeling, which is probably a muscular disorder, or a sensation of the jaw ‘catching’ or ‘getting stuck’, which usually relates to internal derangement of the joint.

Joint noise

- Clicks and other joint sounds are common; they are not significant unless there are other symptoms.

Other symptoms

- Ear symptoms – otalgia, tinnitus, dizziness.

- Headache

- Neck pain.

- ‘Locking’ episodes – inability to open or close the mouth. Inability to open the mouth is more common.

Examination[1]

- Palpate the joint by placing the fingertips in the preauricular region just in front of the tragus of the ear. The patient is then asked to open their mouth and the fingertip will fall into the depression left by the translating condyle.

- Palpate the head, neck and masticatory muscles for areas of tenderness

- Joint clicks or grating sounds on jaw movement may be palpable, or may be heard with a stethoscope over the preauricular area.

- Assess mandibular movement:

- Measure the distance of painless vertical mouth opening, using inter-incisal distance (normal range 42-55 mm).

- Observe the line of the vertical jaw opening: straight or deviating, smooth or jerky.

- Examine lateral movements and jaw protrusion.

- Assess other orofacial structures – salivary glands, oral cavity, dentition, ears and cranial nerves.

Differential diagnosis[1]

- Giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis).

- Cardiac pain (anginaand acute coronary syndromes) can radiate to the neck and jaw, but is usually more acute.

- Dental

- Trigeminal neuralgia.

- Migraine and other causes of headache.

- Herpes zoster.

- Other ENT disorders – eg, salivary gland disorders and ENT neoplasms.

The location of the pain helps in diagnosis. The pain in TMDs is centred immediately in front of the tragus of the ear and projects to the ear, temple, and cheek and along the mandible.

Investigations[1]

No tests may be needed in straightforward cases. Possible investigations are:

- Blood tests: ESR, CRP for inflammation.

- Plain radiographs – show gross bony pathology such as degeneration or trauma.

- CT or MRI scan of the joint. MRI scan shows the soft tissues and intra-articular disc well.

- Ultrasound – this is a useful alternative imaging technique for monitoring TMJ disorders.[4]

- Diagnostic nerve block.[5]

- Arthroscopy.

Management

Overview[1]

- Initial care is usually with conservative treatment, which is effective in most cases.

- Psychological aspects of pain management are important – as with other chronic pain and somatisation disorders.

- Surgical intervention may be used in selected cases, where there is structural pathology not responding to conservative treatment.

- With symptoms of locking: intermittent locking often responds to conservative treatment. A ‘closed lock’ (difficulty opening the mouth) which is long-standing, is more likely to need intra-articular steroid injection or arthroscopy.

Non-invasive (conservative) treatment[1]

Nondrug treatment

- Explanation and reassurance:

- Most TMJ disorders are benign and will improve with non-invasive treatment.

- Rest, patient education and self-care:

- Limit excessive jaw movement by eating soft foods. Avoid wide yawning, singing, and chewing gum.

- Massage affected muscles and apply heat.

- Use relaxation techniques; identify and reduce life stresses.

- Occlusal splints:

- Other treatments:[8][9]

- Acupuncture may be helpful, but the evidence is not conclusive.[10]

- Physiotherapy

- Behavioural techniques – eg, postural training, biofeedback and proprioceptive retraining.

Drug treatment[1]

- Analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or muscle relaxants.

- Antidepressants:

- Tricyclic antidepressants – eg, starting with a low or moderate bedtime dose for 2-4 weeks; if helpful, continue for 2-4 months and then taper down to a low maintenance dose.

- An alternative is a newer antidepressant such as a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor – eg, duloxetine.

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants have been used, but some (fluoxetine and paroxetine) may increase bruxism and are not recommended.

- Benzodiazepines have been used, but there is a risk of dependence.

- One small case study suggested that tiagabine may be helpful for bruxism.[11]

Invasive treatments[1]

- Intra-articular injection, using steroid or hyaluronic acid.[12][13]The effectiveness of hyaluronic acid is uncertain.[14]

- Surgery may be indicated for some patients, mainly when conservative treatments are not successful. It is usually supported by non-invasive treatment before and afterwards.[15]Surgical options include:

- Therapeutic arthroscopy.

- Arthrocentesis

- Removal of loose bone fragments.

- Reshaping the condyle.

- More complex procedures, including joint replacement,[5]depending on the pathology involved.

- Botulinum toxin A (BtA) injections:

- A literature review of BtA use in chronic facial pain suggested that it was no better than other treatments.[16]

Further reading & references

- BAOS British Association of Oral Surgeons http://www.baos.org.uk/

- BOAMS – British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

- Laskin DM; Temporomandibular disorders: a term past its time? J Am Dent Assoc. 2008 Feb;139(2):124-8.

- Atsu SS, Ayhan-Ardic F; Temporomandibular disorders seen in rheumatology practices: A review. Rheumatol Int. 2006 Jul;26(9):781-7. Epub 2006 Jan 26.

- Dimitroulis G; The role of surgery in the management of disorders of the temporomandibular joint: a critical review of the literature. Part 2. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005 May;34(3):231-7.

- Total prosthetic replacement of the temporomandibular joint, NICE Interventional Procedure Guideline (December 2009)

- Scrivani SJ, Keith DA, Kaban LB; Temporomandibular disorders. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 18;359(25):2693-705.

- Wadhwa S, Kapila S; TMJ disorders: future innovations in diagnostics and therapeutics. J Dent Educ. 2008 Aug;72(8):930-47.

- Luther F; TMD and occlusion part I. Damned if we do? Occlusion: the interface of dentistry and orthodontics. Br Dent J. 2007 Jan 13;202(1):E2; discussion 38-9.

- Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L; Ultrasonography of the temporomandibular joint: a literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009 Dec;38(12):1229-36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.07.014. Epub 2009 Aug 22.

- Buescher JJ; Temporomandibular joint disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Nov 15;76(10):1477-82.

- Koh H, Robinson PG; Occlusal adjustment for treating and preventing temporomandibular joint disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD003812.

- Al-Ani MZ, Davies SJ, Gray RJ, et al; Stabilisation splint therapy for temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD002778.

- Michelotti A, de Wijer A, Steenks M, et al; Home-exercise regimes for the management of non-specific temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2005 Nov;32(11):779-85.

- Medlicott MS, Harris SR; A systematic review of the effectiveness of exercise, manual therapy, electrotherapy, relaxation training, and biofeedback in the management of temporomandibular disorder. Phys Ther. 2006 Jul;86(7):955-73.

- Fink M, Rosted P, Bernateck M, et al; Acupuncture in the treatment of painful dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint — a review of the literature. Forsch Komplementarmed. 2006 Apr;13(2):109-15. Epub 2006 Apr 19.

- Kast RE; Tiagabine may reduce bruxism and associated temporomandibular joint pain. Anesth Prog. 2005 Fall;52(3):102-4.

- Bjornland T, Gjaerum AA, Moystad A; Osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint: an evaluation of the effects and complications of corticosteroid injection compared with injection with sodium hyaluronate. J Oral Rehabil. 2007 Aug;34(8):583-9.

- Arabshahi B, Cron RQ; Temporomandibular joint arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the forgotten joint. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006 Sep;18(5):490-5.

- Shi Z, Guo C, Awad M; Hyaluronate for temporomandibular joint disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD002970.

- Dolwick MF; Temporomandibular joint surgery for internal derangement. Dent Clin North Am. 2007 Jan;51(1):195-208, vii-viii.

- Clark GT, Stiles A, Lockerman LZ, et al; A critical review of the use of botulinum toxin in orofacial pain disorders. Dent Clin North Am. 2007 Jan;51(1):245-61, ix.

Education menu

Physiotherapy for Orofacial Pain

A short introductory presentation by Dr Hedvig van der Meer who has recently joined our team:

Our guide to better sleep

By Georgina Gray Good quality sleep is one of our core health pillars. Not only is it vital for energy, mental health and hormone production, it is also important for disease prevention and weight control. We should be aiming for 7-9 hours of good quality sleep every...